March 20, 2012

By Frank Bolin

Where the rays go in northeast Florida, so go the cobia. And so should you.

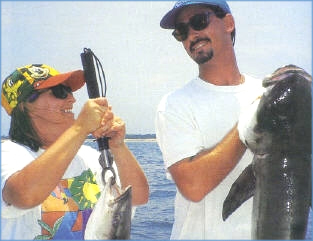

Tracy and John Canada show off the results of an exciting doubleheader on cobia. |

Cobia fishermen are obsessed with manta rays. They dream of that telltale wing-tip, wake or dark shape of a migrating ray, knowing a pod of big cobia may be hanging in the shadow. Light tackle and the thrill of the hunt enhance the challenge of sight fishing cobia along the beach.

Unfortunately, on some days, cruising Florida's Atlantic coastline with eyes peeled for rays is akin to looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. There's a lot of water out there. Many anglers stay close to the inlets, preferring not to make a long run down the beach.

But what if you knew where the rays were heading?

Advertisement

Not far from St. Augustine and Matanzas inlets are a number of areas where the rays—and the cobia—seem to hang out. These are marked by the transition from white sugar sand to orangish coquina shell—the two main types of beach in this part of Florida. Looking shoreward, you can see the changing beach. There are at least four such zones, which I call brown zones, stretched in about 40 miles of coastline.

On a recent trip, I opted to scout for rays in one of these zones. My daughter-in-law, Tracy Canada, was aboard. She's one of those people who come by their fishing talents naturally. Her skill for sniffing out cobia belies her mere one season of experience.

From her point-man perch on the bow, Tracy stood rigged and ready. In one hand she grasped a well-used 15-pound spinning rod. Her other hand held the bowline, using it to keep balance.

Advertisement

We ran on plane, skimming quickly over the slick ocean. For a long time, we saw no sign of rays or cobia. Then suddenly, Tracy's voice stirred her husband John and me from the lull in our scanning chores. “Ray at ten o'clock, about 40 yards away,” she called. I stayed on the helm and John grabbed another rod. Keeping my distance until I could determine the ray's course, I spun the wheel to take them within casting range.

“I can see three or four fish on top of the ray. It looks like there's even more underneath,” John said. The big manta ran deep, at least four feet under the surface, making it doubly hard to discern which individual fish to target.

I held position a steady 15 yards off the ray. “Tracy, you're up,” I offered. “Try to spot the biggest fish. Lead it with your jig and bring it right back in front of its nose.”

She didn't wait for my advice. She picked a target and fired a cast. She brought the 6-inch shadtail straight to a bruiser cruising two feet beyond the ray's left wing. Tracy quit reeling and began dancing the lure enticingly. Watching her presentation, I could tell she'd done her homework. The cast and retrieve were flawless. The big fish turned off the port flank, charged and inhaled her lure.

“I'm on,” Tracy yelled excitedly. The big cobe ran straight toward us. Tracy raced to gather in the slack and keep a tight line. Her fish finally felt the hook, turned and ran for cover under the ray. The rod bowed double as she put on the pressure, hoping to stop her cobia before it made its way around the ray. Such antics would surely mean a lost fish.

“Quick John, see if you can get a cast before the ray sounds. Look out for Tracy's line,” I said in a decibel level better suited for a stock car race. I watched John sail his bait in a tight arc, dropping it two feet off the nose of another cobia.

What's better than a hookup? A double hookup, of course. For a scant second I considered trying for a triple. Common sense got the best of me, and I put the rod back into the holder. My services were needed at the helm. That was obvious, watching these two attempt to keep their lines apart.

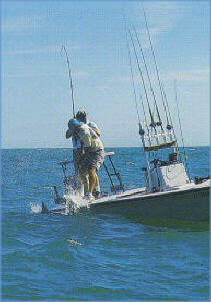

For the next quarter-hour, John and Tracy gained and lost line to these wide-bodied fish. They strained their light spinners to the limit while dancing and maneuvering around my small center console. I kicked the boat in and out of gear, turning port or starboard trying to keep them in the best position for their pump-and-grind style of ocean choreography.

Several minutes later both fish changed strategy. John's cobia headed for the horizon. Tracy's fish sounded and went deep, opting for a straight down, tug-of-war slugfest.

Seeing his chance, John shifted into overdrive, muscling his fish in quickly with short strokes of the rod. The cobia came broadside, giving me a clear gaff shot.

Tracy, on the other hand, had her hands full. Her fish was still 45 feet down, right on the bottom, rubbing its head into the sand in an attempt to dislodge her hook.

“I've never had one fight like this,” Tracy muttered, taxing her 15-pound gear almost beyond its limits. This fish was a bulldog. She gained two feet of line only to lose three.

John piped up, “Don't let him rest. If you're resting, that cobia is resting. Bring it up.”

Hearing John's words, Tracy made her way back to the bow, planted her feet and got serious. She slowly pulled the fish off the bottom with short, six-inch rod pumps. Most of the time her rodtip stayed bowed into the water. She would pull up, get a half crank on the reel and repeat the procedure time and time again.

Her persistence paid off. Ten minutes later, we caught our first good glimpse of Tracy's fish. Unfortunately it saw us at the same time and headed straight back down. It was a good fish, though John and I didn't dare to make a weight guesstimate. On the hookup we thought the fish was around 30 pounds, yet this cobia felt much bigger. Either it was way heavier than we thought, or it had a lot of heart. Maybe both.

Again, Tracy wrestled the cobia up from the bottom. She deftly led it into gaff range. John performed the ho

nors and brought the fish into the boat. Only this cobia wasn't done yet. It twisted off the gaff and sent us scurrying for high ground, while it thrashed and beat its way across the deck.

The fish finally slowed enough for me to get a good grip and slip it into the box. Now we knew why this fish served up so much trouble. It was short and very thick, with plenty of muscle. After rinsing the deck, I took a quick weight and saw it pulled my Boga Grip to almost 40 pounds.

“All right. Let's get this show on the road. It's my turn to cast,” I called to my two triumphant anglers.

I was primed, pumped, and ready for more. We'd found a patch of bottom—a brown zone—where the rays were holding, and it would surely produce more fish in the weeks ahead.

The northernmost zone I like to target is approximately 20 miles upcoast from St. Augustine Inlet, where steep coquina beaches blend into white sugar sand near Ponte Vedra. Heading south, the next zone occurs right at St. Augustine Inlet, where coquina beaches dominate northern stretches and fine white sugar sand is on the south side. The next zone is at Matanzas Inlet, which has white sand on the north side and coquina beaches south. From Matanzas, it is 25 miles to the next transition zone in Ormond Beach.

Before the first migrating cobia begin to show, I spend a day running this stretch of coast scouting out changes from last season and new possibilities. Currents may uncover new bottom structure, such as ridges of hard coquina rock, a composite of the same shelly material you see on shore. Although we have four zones within easy reach, I focus most of my efforts on the north zone, Ponte Vedra, and the south zone, at Ormond Beach. All four areas can and do produce fish, but these two see the least fishing pressure.

What makes these zones better than surrounding waters? To be honest, I am not exactly sure. However, several seasons back, Bill Carr, a Whitney Lab marine scientist, filled me full of scientific jargon relating to the where and whys of manta ray migration. Remember, cobia, along this stretch of coastline, often travel with manta rays. His studies indicated that certain types of plankton, called dinoflagellates, occur in great numbers along these coastal transition zones. Manta rays often hold for days, sometimes even weeks at a time in these areas.

After you've located a productive area, the most critical part of the hunt is the approach. Successful cobia fishing entails more than finding manta rays. Boat positioning and proper lure presentation are key.

Last year I witnessed quite a few anglers and crews defeat themselves after spotting a manta ray. Some would charge the ray, often running wide open until 15 or 20 feet away, pull back the throttle and attempt to cast. This approach does work sometimes, but not very often. The weirdest approach I saw was from fishermen in a “go-fast” hull. This captain gunned his twin 250-horsepower outboards straight over the top of the ray while his anglers dropped their baits, at 40-plus miles per hour, as they whizzed over their target. I never did see them hook any cobia, though it would have been quite a spectacle, I'm sure.

Such run-and-gun antics usually accomplish only one thing: They put the ray down. When mantas get skittish from too much boat traffic, most sound immediately whenever a boat comes close. Use a little common sense when approaching a ray. It pays.

Manta rays are sensitive to rpm changes, especially well into cobia season. After spotting a ray, determine which way it is heading and approach it at steady rpm—somewhere around the 1,000 mark is good. Overtaking a ray with the sun at your back allows for maximum visibility. I instruct anglers on my boat to cast at their first opportunity and keep a close eye on their lure or bait to prevent hooking the ray. The object is, after all, casting to cobia that swim beside, on top of, and under these mantas.

I use artificial lures over 90 percent of the time when casting to cobia. Artificials offer several advantages. Bright colors, chartreuse in particular, are easy to see several feet below the surface, which makes it easier to work your lure and observe a strike. Another reason for using lures is quick presentation. With an artificial, you won't have to divert your eyes from your target to dig around in the baitwell and hook up a livie.

There are many types of lures suitable for cobia fishing. Bucktail jigs, shadtail jigs and surface chuggers are time-proven designs. Choose lures and jigheads with strong hooks, size 4/0 and larger. Avoid trebles. Cobia are hard-fighting fish. A lure with treble hooks is often jacked hard during battle, enough so that many times treble hooks tear loose. Stick with single-hook lures or switch out treble hooks.

Once you get the hang of working a ray, it becomes second nature. Dedication and practice are all it takes to perfect this technique, which definitely results in more fish.

FS