February 17, 2016

By Rodney Smith

Tripletail offer a curious challenge to the fly angler, and they are available around the state.

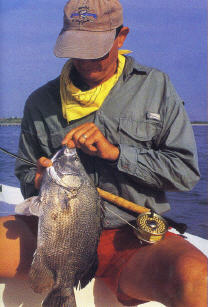

This tripletail, found close to the Canaveral shore, was happy to take a well-presented fly. |

Days and nights of stiff northeasterly winds had hampered our attempts to venture into the windblown Atlantic for more than a week. But now the long wait had ended with the arrival of calm winds and moderate ground swells. Huge patches of sargassum weed had ridden the stiff breezes across the ocean and were now pushed against the currents formed by the inshore shoals of Cape Canaveral. This sargassum, peppered with boards, buckets and coconuts, had created a vast weedline.

I hopped down from my mini-tower while ordering my companion to keep a watchful eye on a piece of flotsam I had just spotted a hundred yards directly to the north. The adrenaline runs high when inspecting new flotsam. Not knowing what you will find swimming under or around it has immense appeal. This is one of the reasons I savor the time I spend sight fishing these waters off Florida's Space Coast.

Most anglers would assume that on a day like this my flyfishing partner and I would have our sights set on catching dolphin, or some other gamefish that prowls the Atlantic Ocean. However, we had something else in mind. We were stalking an adversary that most anglers, even the most serious ones, overlook because of its sullen approach and chameleon-like characteristics: the tripletail.

Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) resembles the freshwater crappie with its rounded dorsal and anal fins extending almost to the tail and the very small face; but this is where their resem-blance ends (except for the fact that both are considered excellent table fare). Found throughout the oceans of the world, tripletail are tough competitors. They can be spotted along all of Florida's coastlines, bays and lagoons. The average size of a tripletail is usually three to eight pounds, but along Florida's Space Coast tripletail of 20- to 30-pound world-record proportions are not uncommon; in fact more IGFA world-record tripletail have been caught outside Port Canaveral than all other places combined.

This fishing excursion would be a particularly memorable one for me because of my companion Art Broadie. Art started his flyfishing career in the foothills of the Catskills of New York and gained his nickname, Blackie, from his exclusive use of the Black Ghost fly, which he used while fishing the Catskill waters for brook, brown and rainbow trout. Art once told me that the reason he preferred the Black Ghost, a streamer fly, over more conventional trout flies is that it caught bigger fish.

Over the last few years, Art's interest in big fish led him to saltwater fly fishing. He now spends the better part of his time between October and May indulging his saltwater passion in Florida. Today was the day we were going to put his skills to work on his first fly-caught tripletail.

We dropped my skiff, Mangle Tangle, into the water at the Central Park Ramp on the south side of Port Canaveral, then idled our way east to the port entrance. Once there, Art and I paid little attention to the surf pounding along the south beaches. We had a plan, and we were sticking with it.

We powered our way ahead, at times flying above the northeast ground swells; but what struck me was the character of the ocean's surface. Except for the rolling seas, it was smooth as silk. As we raced for the open water of the Atlantic, the tip of Cape Canaveral and its miles of shoals came within sight. I pulled back on the throttle and slowed our pace; in the foreground, tools of America's space memoirs lay among the sand and sea oats. Active and abandoned launch pads and gantries, where some of our nation's first rockets were hurled into space, dot the shoreline for miles north and south of the Florida east coast's only cape. These instruments of space travel, past and present, have not altered the beauty of these shores. To the contrary, they add to the backdrop with towering grace.

Just ahead, a raft of sargassum did little to conceal a giant slab of mahogany. I'm not sure what was more exciting, finding this piece of wood from the tropical rain forest or the sight of one lone tripletail hanging in the shade of the plank.

Although this tripletail took a small fly, this mouth can handle bigger meals. |

Art, rod in hand, knelt at the front edge of the skiff. With a practiced and sure hand, he false cast the line he needed then dropped the fly, Greg Poole's root beer Crystal Crustacean, within two feet of our opponent's nose.

The fish turned and slowly tracked the fly. But these fish can be tricky. Just because they turn on the fly doesn't mean they are going to eat. I've noticed they seldom take a fly they follow a long way--and allowing them to follow it too far can create new problems.

Often, once they begin following a fly, they'll sometimes stay with it until they are boatside, then either spook or slip under the boat for a place to hide. Try making a second cast to those fish!

We weren't going to fall for that routine. I hollered at Art to pick the fly up, and once he did so, our target slowly moved back to its mahogany castle.

"Art you're going to have to hit that fish right between the eyes with the fly to get it to eat," I told him. That's one of the ways I've found to get these fish to hit when they are set on following the fly. Put it on their nose so that they hit it instinctively, instead of giving them time to ponder it.

Art looked at me with the "so be it" expression I've grown accustomed to seeing when I give him unconventional advice.

His next cast was a little to the left, and the next was a little to the right. The third cast landed on the fish's head. Art gave the fly a short strip, and the fish cleared the water by three feet after he lunged and took it on the run. Line poured off the reel at a rate that surprised both of us. Before we realized it, our Olympic tripletail jumped twice more. Without a doubt, Art had hooked the most acrobatic tripletail I had ever witnessed. And as quickly as it leaped, it sounded, and carried on a battle more characteristic of a cobia.

Art was prepared for the battle, though, and both his skills and the 10-foot, light salmon rod he was using were up to the task. Both Art and his tackle were veterans in the best sense of the term--the fish didn't have a chance.

"Ten-pound bluegill," I remember one old boy from Georgia saying after he caught his first tripletail. Well, that was some panfish I would like to see. But Art's fish was no fish for the pan and after about eight minutes and a few quick photographs, this tripletail was sent back to his tropical real estate.

Tripletail spawn in the inshore waters of the Atlantic Ocean in late spring or early summer and again in mid-fall. These primeval gamefish lose all their fear when it comes to their mating rituals; normally quite passive, when under their spell of procreation they do strange things: they attack each other, make high free jumps and charge approaching boats.

In past years, there were no bag or size limits and spear fishermen and overzealous anglers took advantage of the tripletail's aggressive behavior and packed their coolers with giant females bursting with ripe roe. However, because of the new MFC (Marine Fisheries Commission) regulations: two-fish limit, 15-inch minimum and no spear fishing for tripletail, this year has been a different story outside Port Canaveral, where anglers enjoyed an outstanding run of buoy-hugging tripletail.

And flyfishers from the Panhandle to Florida Bay are buzzing about the tripletail rebound as well. There are two factors at play here--one, the numbers of fish seem to be up now that strict limits are in place and two, more folks are taking the time to look for them. The result? More fish seen and caught. In the Panhandle waters, spring and fall can be productive times, but inside and outside Apalachicola Bay, August and September can be tops. The fish can be found near shore, around the sea buoys, and offshore under floating debris.

In October, the stone crab season opens and tripletail often keep house at the surface on the downtide side of trap floats. Along the southwest coast and in Florida Bay from Sandy Key west, fly casters cruise along and search the trap floats and after spotting a fish, circle back and approach quietly to present crab, shrimp or baitfish flies with either floating or slow-sinking lines depending on whether the fish are floating or suspended a few feet under.

The same drill is employed when running Everglades National Park markers from Sandy Key to Sprigger Bank near the Keys, or along the nearshore park markers off the Ten Thousand Islands. Sight casting is the rule, although a blind cast or two at a marker can pay off even when fish are not visible at the surface.

The longer the traps are in the water the better--weeds and algae grow on the trap lines, attract baitfish, and in turn, more tripletail. By spring, before the traps have to come out in May, some look like they're growing their own forests. When the spring run of 'tails move in and pick a float, some pretty good catch-and-release fishing can occur. Once the traps are taken out for the year, tripletail will float near the surface around weed mats, pieces of wood and some surprisingly small objects.

Because of these new limits, catch and release has become a common practice. Hit them right and it's not uncommon to release 20 or 30 tripletail per trip. In fact, we caught and released several tagged tripletail more than once over the two-week run, proving that catch and release works.

The prehistoric tripletail were once thought of as an odd, sluggish fish, but have become better recognized in recent years as fine table fare and a hard-fighting gamefish. The new regulations by the MFC should help protect them as they grow in popularity with inshore anglers.

Basic Behavior

For one reason or another many anglers mistake tripletail for flotsam or jetsam while exploring the ocean's surface. Tripletail drift with the ocean currents and spend a lot of time floating on the surface soaking up the sun's rays. Swimming under floating debris, tripletail can be spotted at a distance. Inexperienced anglers often pilot their boats too close to them once located on the surface.

Tripletail are curious fish but will normally spook when approached too quickly. Fish stealthily with a trolling motor or shut down and drift to their position and you can sometimes make more than one cast at the fish. Sometimes they will become annoyed and dive below the surface. If you lay back, keep a watchful eye on the water and wait; they'll reappear on the surface within minutes. When casting to tripletail it's better to let your quarry follow the fly a short distance then recast rather than allow them to approach the boat, in which case they'll either spook or camp under it, making them more difficult to catch. Tripletail are tricky, but more than an interesting opponent!

Tackling Up

Choose your tripletail fly tackle according to the type of flies you plan to toss, and the size of the fish you're likely to encounter. Go undergunned when casting heavily weighted crab flies and casting becomes labor. Get caught undergunned when the fish are the size of manhole covers and you'll land few fish and spend the day digging your flies out of crab trap lines.

Eight- and 9-weight rods are standard and a 10-weight will handle heavy flies and help you horse the big boys away from the trap lines. Go with floating lines when the fish are on top and winds are light. An intermediate or sinking line will help when the fish are hanging deep beneath a trap float, when the surface is rough and the current is ripping, or high winds blow a floating line off course. The only drawback to the sinker is that you'll need to make a good first cast, otherwise, you'll have to strip your fly back to the boat before a second presentation is attempted. To discourage cutoffs on barnacle-encrusted trap lines, use a 30- to 40-pound shock and a 15-pound tippet as a minimum.

Tripletail are opportunistic--they'll normally attack whatever fly you throw, although occasionally they become as selective as can be. You can't go wrong with an assortment of Clouser Minnows, shrimp patterns, and crab flies in various colors and sink rates. Remember the golden rule concerning tripletail and flies: If the fish follows your fly more than a few feet, pick it up, let the fish return to the trap or marker before trying again. With weight crabs or streamers, once the fish follows, let it sink. That will often draw a strike.

FS

First Published Florida Sportsman Nov. 1997