February 27, 2017

By Jeff Weakley

What makes the ideal platform for “driftin' the fifty?” Let's have a look.

Red LED T-top lights cast an eerie but practical glow, preserving night vision long after sunset. Jason Jones, right, brandishes a "swordy".

Red LED T-top lights cast an eerie but practical glow, preserving night vision long after sunset. Jason Jones, right, brandishes a "swordy".

Swordfishing, for all its mystery and danger, is in some ways angling's penultimate exercise in bait-dunking. Leave the abyssal, roiling Gulf Stream for a placid farm pond, and that quarter-ton, sharp-billed majesty for Mr. Whiskers, and there you have it: Catfishing 101.

It is about patience and scrutiny of bottom contours and rodtips. Careful attention to baits. A large predator whose destiny, you hope, is a neighborhood feast.

The scale of the comparison is off the charts, however. Swordfish can grow big. Really big. And they often bite deep, as in hundreds, if not thousands, of feet beneath the surface.

Moreover, the waters they roam give birth to storms and rogue waves that can sink ships, and huge sharks that can eat grown men. No farm pond, the Atlantic Ocean in a roaring summer squall.

To chase swords on a regular basis, you need a vessel capable of hauling sufficient tackle, and more importantly, safely hauling anglers there and back.

Keeping Fish in, the Ocean out

Jason Jones' 33 Dusky departs Fort Lauderdale for a night of swordfishing.

Jason Jones' 33 Dusky departs Fort Lauderdale for a night of swordfishing.

Recently I joined a Broward County crew aboard a beamy center console outfitted to the gills for swordfishing and other bluewater pursuits.

Jason Jones, 35, a consultant in Fort Lauderdale, keeps his 33 Dusky, Rock Lobster II, at a marina close to Port Everglades.

Storage being a prime concern for a Florida swordfish excursion, Rock Lobster is amply provided. Below decks in the bow is a cavernous, 22-cubic-foot well, stretching from stringer to stringer, with foam insulation and three Dometic freezer plates.

Before we headed offshore, I watched as Jason's friends Chris Niesel, of Wilton Manor, and Capt. Bill Springer, of Tamarac, made a wheel-barrow full of 40-pound ice bags disappear into that hold. Ten hours later, I saw one of those bags emerge as a perfect iceberg, a solid block. The others, once plugged into shore power, could be used to stock up drink coolers, bait boxes, even a buddy's boat, for weeks if need be. Jones does a lot of Bimini runs (300 engine hours and 12 trips since taking ownership of the boat in January!). Never having to buy ice in the islands is one less hassle to deal with. Chilling a mature swordfish overnight without a tripping over a fish bag on deck? Double bonus.

Keeping frozen fish inside a hold is one thing, keeping seawater out of the boat is the big thing. Rock Lobster, like others in the Dusky fleet, is designed with an elevated deck and large scuppers which drain directly overboard—not through hidden pipes and hose clamps that route through the bilge. If seawater does somehow find its way into the bilge areas, Rock Lobster was factory equipped with two pairs of 2,000 GPH bilge pumps, all of them on automatic float switches. That's two pumps forward, two aft. But that's not the end of the redundancy: For each pair of pumps, heavy-duty duplex wiring connects one pump to the house battery bank, the other to the starting battery bank.

Which brings us to the heart of a swordfish vessel: a well-planned, secure 12-volt system. Running lights, pumps, sonar, sound system and other utilities during a long drift will draw down even the most advanced batteries. It's essential that engine cranking batteries—your ticket home--are left out of this managed dip.

Jones' vessel had been factory-outfitted at Dusky with a really sweet setup. It has a BEP Marine Voltage Sensing Relay (VSR) cluster switch which automatically isolates the twin starting batteries (Optima blue tops, on an elevated platform in the bilge) from the house bank.

Located inside the console, the house batteries consist of four batteries wired in parallel--again those sealed, absorbed glass mat (AGM) Optimas. When the engines are running and the VSR reads 13.7 volts on the starting batteries, the relay opens and the alternators deliver charging current to the entire six-battery network. Adrift or at anchor, when the starting batteries drop to 12.8 volts, the VSRs open, and the vessel's many systems draw only from the house bank. That includes nav and Hella LED cockpit lights, a Lowrance chartplotter/sonar combo, twin 1,100 GPH livewell pumps, the four bilge pumps, and of course that forward freezer (whose 110V compressor operates on an inverter).

In the unlikely event that a starting battery lacks adequate charge to turn over one of the 300 hp Suzukis, the batteries may be combined through the VSR switch cluster. And in a worst-case scenario, those bilge pumps will draw on whatever current is available.

Managing the Arsenal

[gallery link="file"]

Clockwise from top left: 80-wides; sea anchor deployed; starting batteries with isolator; harpoon; submersible light; house batteries in console.

At the dock, Rock Lobster bristled with 50- and 80-pound-class leverdrag outfits. Penn Internationals and Shimano Tiagras stood by in rodholders circumnavigating the cap of the big Dusky, and in vertical positions abaft the leaning post.

Bent-butt 80-wides are the tools of the trade among many Southeast Florida swordsmen. While the average fish is probably in the 70-pound range, most guys who've been at it a few seasons can recall 300- or 400-pound swords that dumped line at an alarming rate—and that's after eating a squid tethered at the end of 100, maybe 200 yards of line to begin with.

Capacity and the option of serious braking power are comforting when the clicker's screaming and your watch reads 2 a.m. Perhaps even more comforting when you're daytime fishing with almost 2,000 feet of line out!

A big advantage of center console vessels is 360-degree fishing access, and when it comes to open-water drifting, the more forward vee and freeboard, the better. When we reached the fishing grounds, some 10 miles due east of downtown Miami, Capt. Springer deployed an 18-foot Para Tech sea anchor at the bow. It pulled the 33-footer around so that the bow cut smoothly through a 2-foot chop generated by a west wind. (I've seen that same hull dodge 4- to 6-footers behind that Para Tech without a chance of shipping water).

The sea anchor also minimized our easterly creep across a south-to-north drift we'd plotted to intersect a couple of “humps.” Those humps, known by varying names out of different ports, are 100- to 200-foot, round-top domes that pepper the bottom in 1,100 to 1,900 feet of water along the southeast Florida coastline. Swordfish are thought to use these domes as orientation points and current breaks... and indeed we marked some big bodies of baitfish (squid or small tunas, Springer surmised) over a few of them.

Those rodholders all around the gunnels? We fished three baits right off the bow—a flatline and two jug baits, at 120 and 240 feet. Rock Lobster drifted with just enough east to keep the baits away. Along the port gunnel, we fished another jug bait and a pair of “tip rods,” rigged with nothing more than lead weights. The rodholders are all custom-welded to Dusky specifications. All except two: A pair of Tigress swivel-gimbal rodholders port and starboard of the helm station. These neat devices allow the captain to pivot a rod to follow a fish, in the event he's fishing solo or with one buddy.

With a full crew, we were looking at six or more rods, each with a 30-foot leader, 10/0 hook, one to two strobe lights, a big bank sinker, some with plastic jugs and light sticks (see sidebar). Plus, we had a Hydro-Glow light hanging off the starboard gunnel, attracting jacks and other small critters to its luminous blue. As you might surmise, all this stuff doesn't fit very well inside a typical tackle box. Swordfish boats will have large storage hatches into which shoe boxes, oversize tackle trays, and all manner of containers may be stashed away. Jones' 33-footer had twin forward boxes, elevated from the deck. That, plus the console compartment, means no bags lying around on deck.

The Strike Zone

So what happens when one of those vaunted beasts of the deep decides to strike? Will you fire up the engines to follow? Or sit tight and wait for a second bite?

Jones and his pals had been through the drill before. As FS Intern Mark Naumovitz cranked in a small “swordy”—his first—the guys were quick to move rods as needed, and clear space to haul that fish up. Turns out tonight we didn't need that harpoon under the gunnel, or either of the straight gaffs standing by on a T-top crossmember. Really didn't need all that ice, either. Mark's fish looked not much bigger than the 47-inch lower jaw-to-fork minimum. A pair of heavy gloves on the bill, a quick turn of the J-hook, and the fish was returned to the dark depths.

Drifting over a fishy-looking hump off Miami.

Drifting over a fishy-looking hump off Miami.

We had two other probable swordfish bites that night, plus one shark cutoff, and one shark release. The shark had curiously rounded pectoral and dorsal fins, which at first I couldn't place. I thought it an innocuous-looking critter...and at one point I had considered a cool dip in the LED glow behind Rock Lobster II. Reading up on sharks the next morning, my heart skipped a beat. That little dude was a juvenile oceanic whitetip shark. Big ones grow to 13 feet. The term feeding frenzy was invented because of this open-water predator.

On a dark night, adrift in an open boat, one might recall the fate of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, torpedoed in the Phillipine Sea by a Japanese sub in World War II . . . perhaps the cold, gravelly voice of Quint, in Jaws:

“Eleven hundred men went into the water, three hundred and sixteen came out, the sharks took the rest.”

And what sharks were those, you ask?

Yep, sources say oceanic whitetips.

Fun and games, soaking bait for swordfish bite in the deep sea. But, that ain't no farm pond, and that ain't no catfish clattering drag into the blackness. FS

Florida Swordfish Rigs

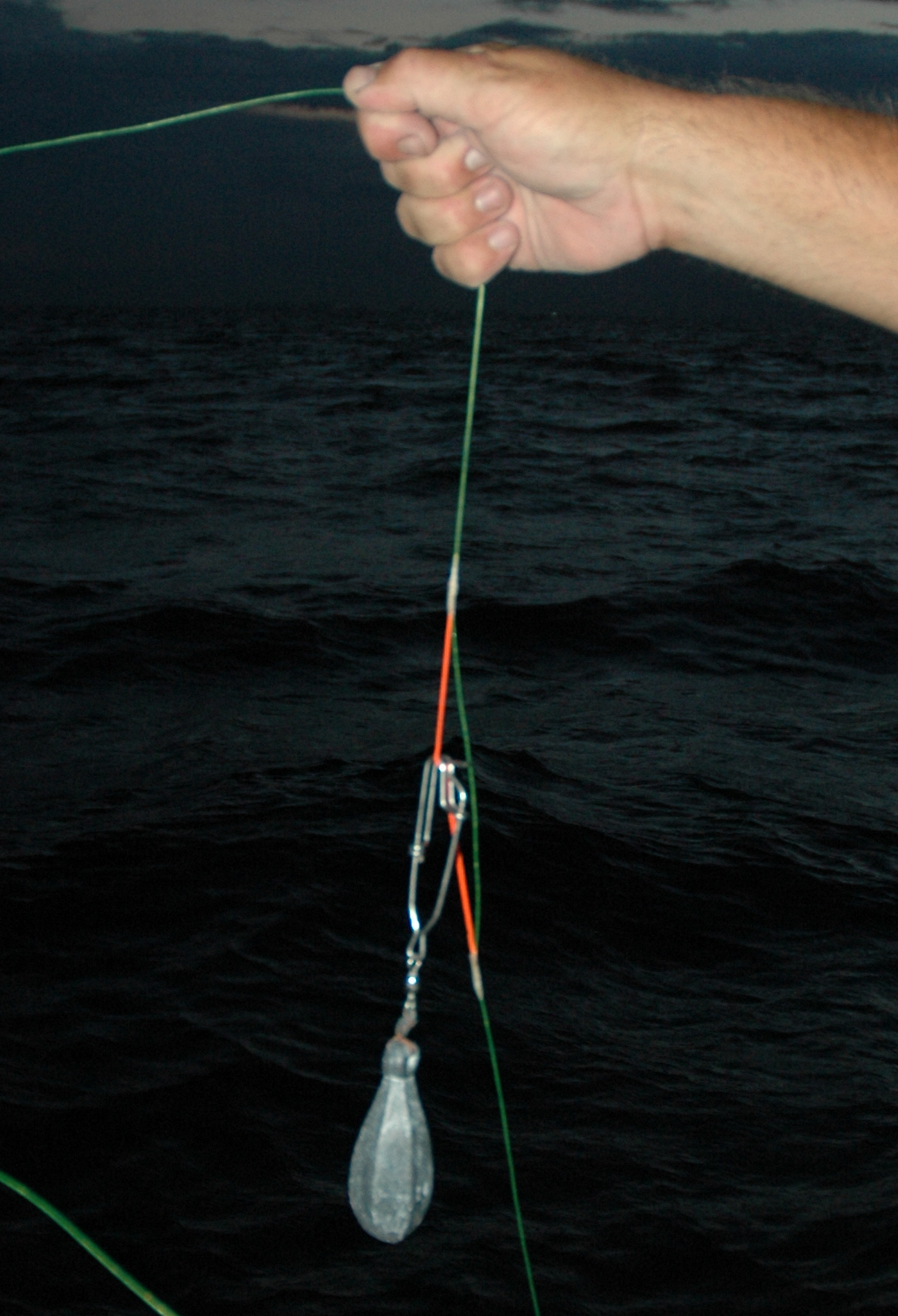

From left to right: Float with light stick; bank sinker in place; strobe and clip.

From left to right: Float with light stick; bank sinker in place; strobe and clip.

Swordfish mainly stay deep during daylight hours, but roam the upper third of the water column at night. They aren't too particular about what they eat, but to maximize your odds you'll need a system for prospecting various depth ranges. Also, various light systems, battery-powered or chemical, seem to help attract swords—though it may be mostly a function of gathering squid and other forage items close to your hooked baits.

So, what about those “jug baits” drifting off Rock Lobster II? These are fishing lines to which a plastic bottle has been tightly hitched with a No. 64 rubber band. The bottle (lid on, of course) acts as a giant float to keep your bait set at a predetermined depth. A chemical light stick taped to the bottle with marine duct tape shines out there behind the boat, so you can keep an eye on the bait.

Nighttime swordfish rigs are often marked at strategic intervals by 6-inch pieces of heavy Dacron whipped to the line at each end with rigging floss or polyethylene braid. Those Dacron loops can be attachment points for the jug, a sinker (anywhere from 6 to 32 ounces), and one or more electric strobe lights. Billy Springer, who does some commercial swordfishing, favors the multi-color flashers, such as the two-color LP Electralume, or Seamaster Disco Deep Drop Light. A typical night-time spread would include baits set at 100 feet, 200 feet, and 300 feet, with a flatline and a tip rod or two, down as deep as the crewman wants. During daylight hours, guys will send baits all the way to the bottom.

The lights and sinker can be attached with longline clips, preferably to the Dacron, instead of the mono. The 80-wides on Rock Lobster had been pre-rigged with 30-foot, 300-pound-test wind-on leaders with Dacron sleeves—and that wind-on sleeve, as well, can hold a longline clip for the sinker and/or a light. --J.W.

First Published Florida Sportsman September 2011