January 01, 2015

By Florida Sportsman

Stewards of the coral reefs have something to sing about.

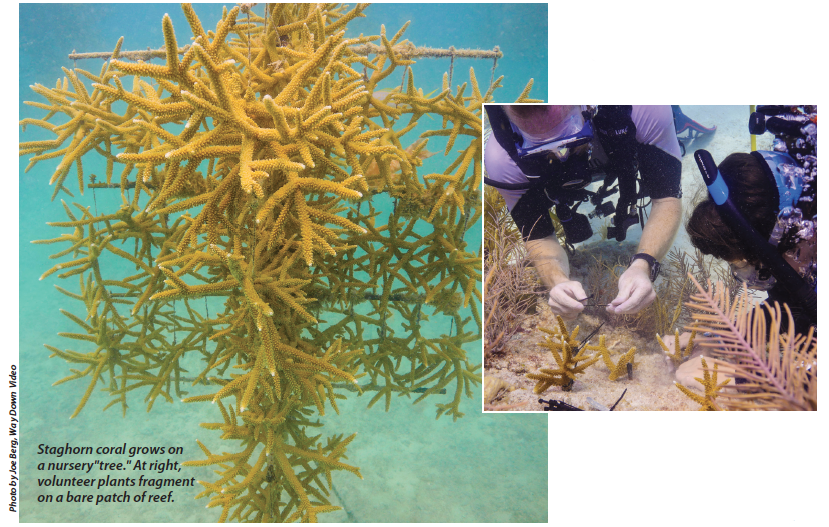

If you've been diving in the Keys recently and happened upon something that looks like a Christmas tree of coral, you're not alone.

Hundreds of volunteers—including combat-wounded veterans, students and the families of fallen soldiers—are helping Mote Marine Lab and the Coral Restoration Foundation grow reef-building corals on “trees” made of PVC and fiberglass that look something like old-fashioned TV antennas.

Fragments cut from coral trees are anchored on hard bottom at designated restoration sites to help jump-start the recovery of staghorn and elkhorn corals in the Keys.

Mote Marine's coral nursery trees hold fragments of staghorn coral that hang like Christmas ornaments from monofilament fishing line. Mote's coral trees can be found in about 20 feet of water over sandy bottom near Looe Key, suspended between buoys and anchors.

The Key Largo-based Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF) is growing colonies of staghorn and elkhorn coral at five nurseries scattered from Key Largo to Key West.

The CRF spent about $383,000 last year growing, transplanting and monitoring staghorn and elkhorn corals. Mote Marine has spent about $100,000 annually in recent years on staghorn coral restoration work.

Money for coral restoration and research comes from a combination of state, federal and private foundation grants, corporate sponsorships and individual donations—including proceeds from the Protect Our Reefs specialty license plate.

The results? During the past two years, the CRF says 80 percent of its transplanted corals have survived, partly because the corals grown in the nursery had already survived the massive die-offs of the previous 30 years.

Mote says 90 percent of its nursery-grown staghorn coral is surviving near Looe Key, though some of its nursery corals showed signs of bleaching (losing their color when they expel symbiotic algae) this summer and are being watched, said Dave Vaughn, director of Mote's Tropical Research Lab in Summerland Key.

Staghorn coral grows four times faster on nursery trees than it does in the wild, said Erich Bartels, director of staghorn coral restoration for Mote.

Nursery-grown corals are needed because the two fast-growing Acropora corals—staghorn and elkhorn—have suffered from massive die-offs since the 1980s.

Populations of the two corals, which once grew like weeds on Keys reefs, have dropped by as much as 97 percent throughout their growing area.

Higher water temperatures from global warming, diseases such as white band disease and pollution from land have contributed to the widespread loss of the Acropora corals.

Both staghorn and elkhorn corals were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2006. In August, NOAA listed as threatened another 20 coral species, including five that grow in the Caribbean.

Although high summer water temperatures are still stressing Keys corals and causing them to bleach, the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission reported welcome news about transplanted corals in August: They're spawning.

The FWC said nursery-grown staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) was reproducing at Tropical Rocks, about 4 miles off Marathon, by releasing millions of gametes into the water during the annual mass coral spawning that occurs around the full moon in August.

Most staghorn and elkhorn reproduction occurs asexually when pieces simply break off and attach themselves to hard bottom.

When sexual reproduction occurs through spawning, coral larvae drift for days before finding a place to settle. Spawning disburses the corals, builds genetic diversity and is a sign that transplanted corals could repopulate reefs on their own.

Mote and CRF have transplanted some 35,000 pieces of nursery-grown coral at restoration sites (and plan to boost that number significantly in the coming year). But that's no guarantee that elkhorn and

staghorn populations will fully recover in the Keys.

The goal is to reestablish pockets of corals that are genetically diverse and able to withstand stress factors, such as high water temperatures and nutrients from

polluted runoff, said Tom Moore, coral restoration coordinator for NOAA in St. Petersburg.

“We may be beginning to impact little patch reefs here and there, but it's still a resource-limited operation,” Moore said, noting that funding for coral restoration work varies widely from year to year. “We're building coral nurseries to reseed the reef and increase genetic diversity.”

Moore said biologists are applying what they've learned from growing and transplanting slower-growing species, such as star coral.

Not surprisingly, fish have discovered the Keys coral nurseries.

Black grouper, mutton snapper and large numbers of yellowtail snapper are attracted to the staghorn coral trees at Mote's nursery near Looe Key, Bartels said.

The growth of staghorn coral on the reefs will “create new diverse structure that will bring in other fish,” he said.

Moore said the antler-like branches of staghorn coral grow thick enough to give juvenile fish a place to hide until they're large enough to escape predators, including the voracious, non-native lionfish.

Mote Marine and the CRF are working to involve volunteers in coral restoration projects as much as possible, partly to raise awareness about the plight of coral in the Keys.

Volunteers who worked on coral restoration with Mote Marine this summer included amputees who are members of Combat Wounded Veteran Challenge as well as members of Gold Star Teen Adventures, a group that provides adventure camps to youths whose parents died in the line of duty.

Students from Florida Keys Community College and members of SCUBAnauts International, which involves teens in marine research and conservation projects, also assist with the coral restoration work.

The CRF allows recreational divers to participate by taking a short training class and diving with a commercial dive operator. Divers can sign up for coral restoration dives through the organization's website, www.coralrestoration.org.

Recreational divers are helping to track the status of coral through the Bleach- Watch program (www.Mote.org/Bleach- Watch), which collects reports from Key Largo to the Dry Tortugas.

BleachWatch reporting forms ask divers to note the time, date and coordinates of their dive as well as weather conditions and the bleaching status of corals observed, from slightly pale to totally bleached white. BleachWatch volunteers also report observations of corals that show no signs of bleaching.

- Willie Howard