February 17, 2012

By Harlan Franklin

Advances in techniques and tackle over the past few years have made a definite flyrod fish out of the wily permit.

Velcro crabs are the latest hot crab patterns.

|

For two hours we had shots at feeding and tailing fish every six or seven minutes. I don't remember a morning when I'd seen so many calm, feeding permit.

I was poling while my friend Dave was casting. Dave is a super fly fisherman from Islamorada, and a whiz at catching bonefish on a fly. But expertise with bonefish was giving him trouble now, because he kept using bonefish techniques on permit.

A fish would appear a hundred feet away, working its way toward us, tail up, then down, then up again as he scoffed up goodies off the bottom. I would swing the bow of my skiff to the right, giving Dave plenty of room for his back cast. When the fish moved to within 60 feet, Dave would make his cast, placing the fly just where he wanted it. The trouble was, he wanted it in the wrong place.

Every time he cast he dropped the fly several feet in front of the fish. Great for bonefish. Not great for these slow moving, feeding permit.

The best way to catch a feeding permit on a fly is to hit the fish right next to the nose. Let the fly sink, and hope the fish takes it while it's sinking or as it hits the bottom.

Sound crazy?

Veteran Key West permit guides Gil Drake and Tom Pierce will tell you that over half of their clients' fish are caught this way, without the angler so much as twitching the fly.

You can look at it this way: Put the fly so close to the fish that he doesn't have time to think about it, only time to react. Give a permit time to consider a fly, and the chances of him taking it are slim.

I explained this to Dave, and he agreed--and conceded that after years of casting flies to bonefish, leading them was so ingrained in his head that he just couldn't make the fly land so near a fish. I understood his problem. Many other good anglers have had the same experience. It's natural to worry about the fly spooking the fish when it lands on them. And that does happen sometimes. You've simply got to ignore the fish that spook and play the odds. You'll have more takes casting close than you will leading the fish.

Put the fly on the permit's nose--that means two feet or less in front of the fish.

If the fish rejects the fly, retrieve it erratically, then stop retrieving and let it fall to the bottom, where the fish will have an opportunity to pick it up. The best way to know for sure when the fish picks the fly up is to see him do it. Normally, the fish is moving toward the boat and/or the boat is moving toward the fish. With the gap between the fish and fisherman constantly closing, it is difficult to feel exactly what's going on with the fly. If you can't see the fly, or see the fish eat the fly, you need to keep the line tight enough so you can feel him take the fly.

That's tougher with permit than most other fish. He's prone to pick the fly up very gently, then quickly realize it's really not a crab, and spit it out.

As fish go, permit can be pretty smart. But there are some things you can do to give you an edge.

During the retrieve, always watch the fish. If you see his head go down near where you think the fly is, get any slack out of the line at once, and if you feel some resistance, immediately set the hook with a long strip.

Some anglers, when they feel the permit is about to take the fly, sweep the rod sideways to tighten the line instead of stripping. The sweeping method may work for some, but it does present one glaring weakness. Suppose a permit chomps down on your fly at the end of the sweep. He better chomp down hard enough to hook himself, for with the rod out to your side at the end of the sweep, you won't have enough leverage to set the hook.

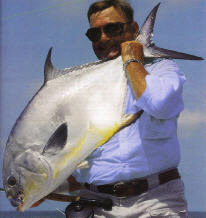

The right conditions, a good presentation, and teh right fly does the trick.

|

When you make the strip strike, remember to keep the rodtip down right at the water's surface and pointed toward the fly.

The sink rate of your crab fly is very important. Many anglers, when fishing for permit, have two rods rigged with flies of different weights and sink rates. They will use the slower sinking fly on shallow flats, and switch to a faster sinking fly on deeper flats. It's a strategy that can pay off.

Traveling permit present an entirely different challenge to the angler. Your odds of hooking one of these fast-moving fish is much less than that of hooking a feeding fish, and casting to them requires a different tact than casting to feeding fish.

You need to lead traveling fish by 10 or even 15 feet, depending on how fast the fish are moving and how fast your fly sinks. The ideal presentation has the fly sinking right in front of the permit.

The window of opportunity is usually a very narrow one with any permit you cast to. Here's a common scenario:

The angler is poised on the bow, ready to cast. His companion, poling the boat, sees a fish. "Permit, twelve o'clock, 100 feet, moving right at us," he says. As the fish moves toward the boat and the boat moves toward the fish, the poler kicks the boat around to give the angler a clear back cast.

"He's at ten o'clock, 80," he says. The problem is, the poler, with his better vision from the platform, sees the fish but the angler has yet to find it. The boat has now lost momentum, but the fish is still moving toward it. The angler finally sees the fish at 60 feet, makes two back casts, then casts the fly to the fish, now at 50 feet.

If you haven't experienced this sequence, it's difficult to tell you how fast it all happens. And the adrenaline pumping through your veins makes it seem to happen all that much faster. This window gives you one shot at the fish. Maybe, just maybe, one more if you're off target the first time and can put the fly back out immediately. Take four or five false casts and the fish will likely be gone before you make your first presentation.

Often, especially on calm days, the motions of casting will spook the permit. The more back casts you make the more chance of a spooked fish. Remember, speed and control catch permit, not long casts.

In the late winter and spring, when it's blowing 15 knots, most permit are caught on relatively short casts--40 feet or less. On windy days the fish aren't so spooky, and easier to catch on a fly. A quick, accurate short cast will get the job done for you. On these days, a full-size crab fly is best.

It's different in the fall and summer. Then, many days have only a light breeze and long, accurate casts are a big plus. On flat calm days you may need to cast like Rajeff to make a presentation before the fish spooks.

When you're planning a permit trip anywhere from Biscayne Bay to Key West, consult your Florida Sportsman Tide Guide before choosing your dates, but consider that in the winter and spring, tides are not nearly as important as the weather. If the weather is fishable, you go, and most days you go you'll find permit.

The more you go the more you'll know, and the more you know the more fish you're going to see. Again, tides are a factor in the spring, but not nearly so much as in the fall. If you have a choice, March can be super. If it's a warm February, that can be even better.

Fall fishing is different, and October can be a very good month, both fishing-wise and weather-wise. Permit can be scarce during periods of small tides, then pop up all over the flats with big tides.

Let's look at Key West tides as an example.

The height of the tides is crucial this time of the year. Crack open your FS Tide Guide and look at October. This month and next, weather permitting, the best permit fishing will be on the oceanside flats, from Sugarloaf Key all the way to the Marquesas. Most of these flats are shallow, and it will take a 1.8 or better tide to move fish up on the flats. And a 2.0 tidal height is even better. For example, this October's good tides are at the beginning, middle and end of the month. Plan your permit fishing expedition around these.

Again, the height of the tides isn't as important in the spring. One big factor is the great fishing you'll find on the Gulfside flats. On many of these flats, the best fishing is often on little tides, with a height of 1.4 to 1.6. It would be impossible to pinpoint any one Gulfside flat as being better than any other. There are over 30 miles of flats from the Content Keys to the Marquesas, any of which will have permit on them at times. However, for consistency, the flats from Jewfish Basin west to Boca Grande Channel are super permit flats. Finding fish here is not complicated, just choose an area where the water is two to three feet deep and start poling. As the tide rises, move farther up on the flat, and as it falls, move out to the edge of the flat.

On both the Atlantic and Gulf sides, during low water periods when the flats are too shallow for fish, you'll find depressions of different sizes and depths, especially those with openings to deep water, holding permit when the tide is low.

Sometimes the fish will feed along the shallow edge and sometimes they will school up and hold out in the deeper water. There, depressions can vary in size from one acre to many times that, and usually range from three to five feet deep during low tide.

If you are having difficulty finding fish when the tide is low, look for these areas, and when you find one, give it a careful going over. And don't be discouraged if there are no fish there. Find another depression and work it. These areas don't all hold fish, but when you find one that does, chances are there will be fish there again and again under similar conditions.

The majority of these depressions are on the Gulfside from the Lower Harbor Keys to the Marquesas Keys. There are a few places where permit like to feed in water so shallow that their fins poke out of the water. It's a wondrous sight to behold, but if you want to catch a permit on a fly, best you stick to the fish in a little deeper water. A permit in three feet is much easier to catch than one in a foot of water.

As good as the Gulfside flats are in the spring, don't overlook the oceanside flats. Any time you have big tides permit are going to be on these flats, especially those west of Key West. During times with small tides, when the fish don't get up on the flats, work the edges. The inside edge is usually better than the ocean edge, but not always. Oftentimes wind and water clarity dictate which edge to fish.

It seems that every month or two there's some hot new permit fly. Most of the Key West and Lower Keys guides pretty much stick with the Merkin pattern--it's a classic, and it works. They do, however, change the size and weight of the fly to fit the circumstances. Again, sink rate is important. Throw a crab out in shallow water and watch how quickly he swims to the bottom.

Many anglers make the mistake of thinking crab patterns are just for permit. Remember, many fish eat crabs. If you spot a bonefish or tarpon, give that fish a chance to eat your crab fly. If he's in a feeding mood, chances are good you'll get a hookup.

The choice of tackle is fairly standard, but subject to the angler's individual preference. Some go as light as an 8-weight rod, some as heavy as an 11-weight. Personally, I like an 8-weight for my smaller, lighter flies, and a 9-weight for the bigger, heavier flies. However, there are times, like on windy days, when a 10-weight is more practical. The presence or lack of wind is a dominant factor in fly fishing for permit, demanding flexibility in tackle.

A standard weight-forward floating line is used by most experienced Keys guides and anglers and most use a line one size larger than what the rod calls for. There are a couple new alternatives some have tried, with mixed results. One is the Scientific Anglers Mastery Stillwater slow-sinking clear fly line. Coat this line with line dressing, and it will float for you. There is also the Monic, a new clear, floating monofilament line now on the market. It's tough to keep up with the location of your fly with these lines, but I believe both have great potential for use on calm days, or when you're wade fishing. It helps to use a highly visible fly when you are using a hard-to-see fly line.

Under normal conditions, permit are not especially leader shy. A 16-pound-test leader will work fine. If you want to go lighter, wait until after you've landed your first fish. When it's breezy, an 8- to 9-foot leader is plenty long. Remember, you're going to lay the fly right on the fish, making long leaders unnecessary. When it's calm, or just a light breeze is blowing, go to a longer leader, like 10 feet, and a smaller fly, such as a Merkin tied on a No. 1 or No. 2 hook. Most of the calm days will be in the summer and early fall. Then you'll have the added advantage of seeing more bonefish than in the winter, and bonefish love small crab flies. Stay flexible with your flies, and after several rejections, start changing the size, weight or color.

Permit offer a major challenge to the saltwater fly fisherman. They are just plain tough to catch on a fly. Baseball and fishing great Ted Williams said many years ago that permit were not a flyrod fish. The improvements in technique and tackle in the past 10 years have changed that. Now, permit are the ultimate challenge to the saltwater fly fisherman. Multiple catches in a day is a reasonable goal for an accomplished fly fisherman.

Sometimes skill, tackle and techniques are secondary to plain old luck. I'll never forget the time I motored up on a flat to give it a try. Just as I cut the engine, a spooked permit darted away from the boat. My angler began to work his line out in preparation to cast. He dropped the fly in the water 40 feet from the boat and stripped another 10 feet from the reel. He then attempted to lift the fly line out of the water to work more line out. He tried to lift the rod and to his surprise, it wouldn't lift. He was even more surprised when the line began zinging off the reel. We couldn't imagine what had taken the fly, but guessed a cuda or shark. To our surprise we spotted a permit crossing a shallow white spot, trailing a fly line. Twenty minutes later we landed a beautiful 15-pound permit. I don't know if this was the same fish we had spooked. I do know the fish was hooked just seconds after I cut the engine.

I didn't tell my partner what Vic Dunaway had told me many years ago, but I sure did think about it. "I'd rather be lucky than good anytime" was Vic's sage observation. So, when you seek your permit on a fly, may luck be with you.

Sportsman's Classic Originally published October 1997.

FS